In the 1960s, the city of Detroit stood at a crossroads of industrial might, cultural innovation, and mounting racial tension. As the symbolic heart of the American automotive industry, the city was home to powerful manufacturers like Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler, which dominated the local economy and shaped Detroit’s identity as the “Motor City.” These companies provided well-paying, unionized jobs that drew tens of thousands of Black migrants from the rural South during the Great Migration. For many African Americans, Detroit represented the possibility of economic stability, home ownership, and upward mobility. By the middle of the 20th century, the city had become a hub of Black working- and middle-class life, with vibrant churches, community organizations, and Black-owned businesses contributing to a growing sense of pride and self-determination.

However, Detroit’s industrial prosperity masked severe racial inequalities. Black residents were often confined to overcrowded, underfunded neighborhoods due to redlining and discriminatory housing covenants. Schools remained de facto segregated and unequal, and Black workers were frequently excluded from skilled labor or supervisory positions. Despite contributing significantly to Detroit’s economy, African Americans were systemically denied full access to its benefits. City policies, including urban renewal projects and freeway construction, often displaced Black communities in the name of progress, worsening housing shortages and community fragmentation.

By the early 1960s, economic decline had begun. Automation and suburbanization started to erode the manufacturing base, and white residents increasingly fled to the suburbs, taking with them tax revenue and political power. As jobs disappeared and services deteriorated, Black communities faced increasing hardship. Meanwhile, tensions with the overwhelmingly white police force became more volatile. A pattern of over-policing, harassment, and brutality deepened community resentment, particularly among younger generations who saw little improvement despite the promises of the Civil Rights Movement.

This accumulation of frustration and systemic neglect exploded in July 1967 when a police raid on an unlicensed Black-owned bar triggered five days of rebellion. The Detroit Uprising of 1967, also known as the 12th Street Riot, resulted in 43 deaths, over a thousand injuries, and thousands of arrests. Entire blocks were burned, and the National Guard and U.S. Army were called in to restore order. The uprising shocked the nation and exposed the deep racial fault lines in northern cities, challenging the myth that civil rights issues were confined to the South.

Despite this backdrop of unrest and inequity, Detroit remained a center of Black cultural innovation, especially in music. It was in this charged social and economic environment that Motown Records rose to national prominence, offering a new model of Black artistry, ownership, and success.

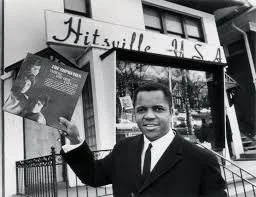

Amid the industrial heartbeat and racial tensions of 1960s Detroit, a musical revolution was taking shape just blocks from the city’s auto plants. In 1959—the same year that Don Kirshner launched Aldon Music in New York’s Brill Building—Berry Gordy Jr., a former boxer, assembly line worker, and Korean War veteran, borrowed $800 from his family to start a record label. He rented an eight-room house at 2648 West Grand Boulevard, naming it Hitsville U.S.A., with living quarters upstairs, office space on the first floor, and a modest studio built into the garage. This house would become the nucleus of what would later be called Motown, a name Gordy coined by blending “motor” and “town” to honor Detroit’s automotive legacy.

Gordy envisioned building a record company with factory-like precision, a concept shaped by his experience working on the Ford assembly line. Influenced by Booker T. Washington’s emphasis on economic self-reliance and raised with a belief in the tenants of capitalism from his middle-class upbringing, Gordy organized the company with industrial efficiency. Writers wrote, singers sang, musicians played, and producers supervised the recording process. These roles were rarely crossed. Talent was viewed as labor, paid to perform rather than to conceptualize. While this strict division frustrated many artists—leading some to leave when their contracts expired—it generated a remarkable series of hits in the company’s early years.

Motown’s first imprint was Tamla Records, followed by the official Motown label in 1961. Additional subsidiaries soon followed, including Gordy Records in 1962, Soul in 1964, VIP in 1964, Rare Earth in 1969, and Black Forum in 1970. Gordy personally trained the label’s early songwriters and producers, instructing them to craft music that appealed to both Black and white audiences. His first successes came with acts such as The Miracles, The Marvelettes, Mary Wells, and Martha and the Vandellas. These performers were often discovered at open mic nights, school talent shows, and local auditions.

In December 1960, Motown scored its first major hit with “Shop Around” by Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. Co-written by Gordy and Robinson, the song reached the Top Ten and established Motown as a national force. Gordy then built a powerhouse creative team that included the songwriting and production trio Holland-Dozier-Holland (H-D-H) and a world-class studio band, The Funk Brothers.

Musically, the “Motown Sound” was a unique blend of gospel emotion, pop song structure, and strong rhythmic drive. Gordy and his team used multi-track recording to layer textures, combining orchestral instruments, tambourines, handclaps, saxophone riffs, melodic bass lines, and Latin- or jazz-influenced percussion. The songs were also built around catchy hooks—memorable melodic or lyrical phrases that repeated throughout the track, making them instantly recognizable and easy to sing along to. Gordy avoided suggestive lyrics and gritty textures, crafting songs that could appeal to white teenage audiences and limiting the potential for watered-down cover versions by white pop artists.

By 1963, Motown’s single sales in the United States were second only to RCA and CBS. The label’s roster continued to expand, including The Supremes, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, The Temptations, The Four Tops, Junior Walker and the All Stars, and later, the Jackson 5. Motown evolved from a regional label into a global cultural force. Its publishing division, Jobete, became the most successful music publishing company in the country. By 1967, Motown had sold more singles than any other record company in the world. Approximately 75 percent of its releases had reached the Top 40. National publications such as The New York Times and Fortune profiled the company, solidifying its reputation as both a commercial juggernaut and a cultural milestone.

Motown’s songs focused on themes like love, heartbreak, joy, and aspiration and other universal messages to appeal across barriers of race and class. Although the label’s catalog remained largely apolitical during the 1960s, its cultural impact was unmistakable. The music, rooted in gospel tradition and supported by a carefully crafted public image, introduced positive Black role models to a national audience. In the midst of Detroit’s economic decline and rising racial tensions, Motown represented Black excellence, discipline, and entrepreneurship. It helped bridge racial divides through music and showed the world what was possible when Black talent was given the space and support to thrive.